When the Holy Cross Refused to Leave Alitagtag to Save Its Inhabitants from Taal Volcano

There are many folkloric stories about the Holy Cross, patron of the towns of Alitagtag and Bauan, the former incidentally once part of the latter. One of the most fascinating of these was a story set during the 1911 eruption of Taal Volcano, among the most destructive in recorded history.

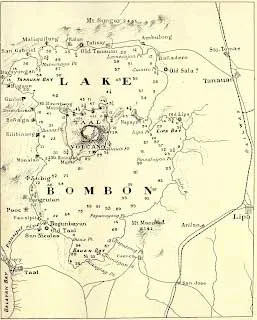

An estimated 1,335 people were killed by this horrifying event, many erstwhile living on the main island crater trapped by the base surge2which also affected the inhabitants of the nearby towns of Talisay, Laurel and Agoncillo.

For a narrative on the flow of events leading to and during the 1911 Taal Volcano eruption, READ: “First-Hand Narrative of the Violent 1911 Taal Volcano Eruption which Killed More than a Thousand People.”

Fortuitously, despite its proximity to the volcano, the town of Alitagtag was spared from the devastating effects of this eruption, the ashes and debris of which fell as far away as the capital city of Manila3. That the town was spared, its inhabitants attributed to a miracle involving its patron, the Holy Cross.

RELATED STORY: “The Legend of the Miraculous Holy Crosses of Alitagtag and Bauan.”

How it came to be seen as a miracle we get details of from a folkloric story contained in the so-called “historical data4” written in the early 1950s for the barrio of Balagbag in Alitagtag. According to the story, when the volcano started “spitting forth molten lava, red-hot rocks and ashes” late in January of 1911, local church authorities immediately met and decided it would be prudent to temporarily move the Holy Cross to Bauan for safekeeping while the threat from the eruption was ongoing.

But the Holy Cross refused to budge. A large crowd had gathered in the town to witness its transfer, but when a sacristan was asked to remove it from its pedestal, he was astounded to find that he could not lift it. Some onlookers were skeptical and themselves volunteered to lift the Holy Cross, but “all their efforts were to no avail.”

RELATED STORY: “The Folkloric Origin of the Subli Dance of Batangas from a 1916 Ethnographic Paper.”Stunned, everyone fell to their knees, presumably in awe and prayer, including the small group of skeptics. The priest decided to abandon the plan to move the image and, instead, led the faithful in prayer.

That same night, the Holy Cross itself showed why it refused to leave its own pedestal. The folkloric story went:

“When night came, the volcano stepped up its activity. The sky above became a terrifying spectacle as huge balls of fire flew thick and fast. All of a sudden, the people of the town began to witness an awe-inspiring phenomenon. The Holy Cross was visibly high up, soaring like the present-day man-made machine. It glided from East to West and back. As if by spell of magic, the cloud of fire rolled fast to the north. Distinctly, the speechless folks below say how the town was saved from imminent destruction and death. This miracle of the Holy Cross recurred during the following days until the monster of Taal returned once more to its peaceful slumber. When the catastrophe was over, thousands of casualties were reported from all the neighboring towns, both far and near, but this town, though literally a stone-throw only from the volcano, suffered no casualty at all. This was all because of the miracle of the Holy Cross.”

There are likely scientific explanations as to why Alitagtag was spared, but that “the cloud of fire rolled fast to the north” was corroborated by one Jay Robert Nash, who was with a group of American engineers encamped in Bayuyungan (presently Laurel, Batangas) north-northwest of the lake.

Nash described the blast heading their way early in the morning of 30 January:

“Smoke came out of the crater in dense clouds. The rumbling noise grew louder and louder, and then became a heavy report (in this context, like the sound of a big gun firing). I then saw the mud issuing from the crater as a cloud. In a few seconds, I saw this cloud drifting across the lake toward our camp. Our camp was then swept by a heavy wind which broke the tent ropes and threw the tent into the air. This atmospheric disturbance threw me a distance of about fifteen feet. A rain of ashes fell about eight inches deep, the air was oppressive, and we gasped for breath for twenty seconds5.”

Notes and references:

1“At Risk: Natural Hazards, People's Vulnerability, and Disasters.” Published 1994 in New York, by Piers M. Blaikie, Terry Cannon, Ian Davis and Ben Wisner.2A base surge from a volcanic explosion is made up of clouds of gas and ashes that shoot outward from the source of the explosion and move close to the ground. Volcano Discovery.

3Blaikie, ibid.

4The details of the alleged miracle of the Holy Cross are taken from the “Balagbag, Alitagtag, Batangas: Historical Data,” online at Batangas History, originally from the National Library of the Philippines Digital Collections.

5“Darkest Hours,” by Jay Robert Nash published 1976 in Maryland, USA.