Santo Tomas, Batangas in the 19th Century as Described by a Spanish Historian

Continuing with the series in this web site on 19th century Batangas as described by the former government official and historian Manuel Sastron in his book “Batangas y Su Provincia1” (Batangas and Its Province), we move north to the now-bustling town of Santo Tomas.

Bustling, the town was not in 1895 when Sastron published his book. It had a population of “11,329 souls” (compared to 179,844 as per the 2015 Philippine Census) and was 46 kilometers from the capital town of Batangas. The actual distance as the crow flies is roughly 42 kilometers; so allowing for road curvatures, this was probably accurate.

The town was bordered to the north by the province of La Laguna (as Laguna used to be referred to during the Spanish era) and Mount Maquilin (Makiling as we know it today), to the west by the lake of Bombon2 (Taal Lake) and the south by the town of Tanauan.

The main road from the town of Batangas leading to the province of La Laguna and Manila cut right through Santo Tomas, dividing it into two parts. In the town itself, the roads could become really bad during the rainy season. These roads had four bridges, even if Sastron wryly observed that only two of these were deserving to be called such.

|

| The chimney of an Spanish-era sugar mill in Sto. Tomas. Image credit: University of Michigan Digital Collections. |

The one called the Biga Bridge, under construction by the Bureau of Public Works, would be a “magnificent one,” however, when fully completed according to him.

Santo Tomas was an “advantageous” place to live in, said Sastron. The air was fresh and, therefore healthy for the town’s inhabitants. Of the town’s 240 or so houses, 12 were built with sturdy materials, i.e. with stone. The others were likely bamboo and nipa houses.

There were no major rivers that flowed through the town; albeit there was a stream called the San Juan from where the townspeople fetched good clean water for drinking and other domestic uses.

Farther away from the town, closer to Mount Maquilin from where they originated, were nine small streams called Biga, Cabaong, Lagnas, Cocac, Pañgao, Capos, Culit, Dipangla and San Piro along with minor estuaries.

|

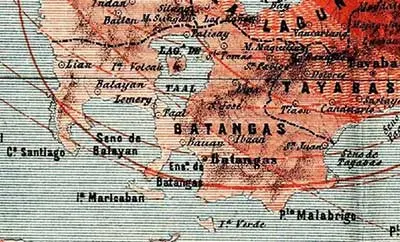

| This 1880 map seems to show that Santo Tomas did indeed have an outlet into Taal Lake. Image source: Jigger Gilera, M.D. and History of Batangas on Facebook. |

The people of Santo Tomas planted their agricultural fields with rice, sugarcane, peanuts, garlic and oranges3. These fields were dependent on rain, although Sastron suggested that they would be easy enough to irrigate using water from the San Juan River.

The crop yields in Santo Tomas were similar to those in Tanauan three kilometers south, but the wages paid to the field workers were slightly cheaper. However, if these same workers brought their farm animals with them, they could actually earn more.

There were several mills in the town to process the sugarcane from the fields. The manufactured sugar, in turn, was exported to Calamba, from where it was presumably taken by boats through Laguna de Bay for sale in other towns.

Santo Tomas’ church and convent were built with sturdy materials, wrote Sastron. The church was the life’s work of Father Miguel Garcia, while the convent was built under the initiative of Fr. Enrique Aranda. Both edifice’s wonderful interiors were due to the efforts of Father Felix Garces.

At the time of Sastron’s visit, Fr. Felix Garces had just been replaced as parish priest by the young Fr. Candido Puerta who from the very first time he assumed the position was “very sympathetic and sincere” and fully deserved to be parish priest. The parish was administered by the Recollect order.

Santo Tomas had a court house made with sturdy materials, but the primary schools were poorly built. For a few months, there was no school for young girls, albeit there was a teacher who taught privately. The situation was eventually remedied when the civil office opened an official school for girls and appointed a teacher with a normal degree4.

The town had a cemetery with a high stone fencing and a chapel inside it. Its location, Sastron noted, was too close to the town itself.

There was a degree of crime in both Santo Tomas and Tanauan, although Sastron noted that the rate of this “diminishes every year.” Still, he went on, constant vigilance was required “to prevent the punishable acts that are committed.”

2 An 1880 map seems to show that Santo Tomas indeed had an outlet in Taal Lake.

3 These were mandarin oranges called “sinturis” or “dalandan” in Tagalog.

4 A “normal” school was a training school for teacher so a “normal degree” was a teacher’s degree.