2nd Testimony of Conchita Lualhati on Japanese Atrocities Committed in Taal, Batangas in 1945

[TRANSCRIPTION]

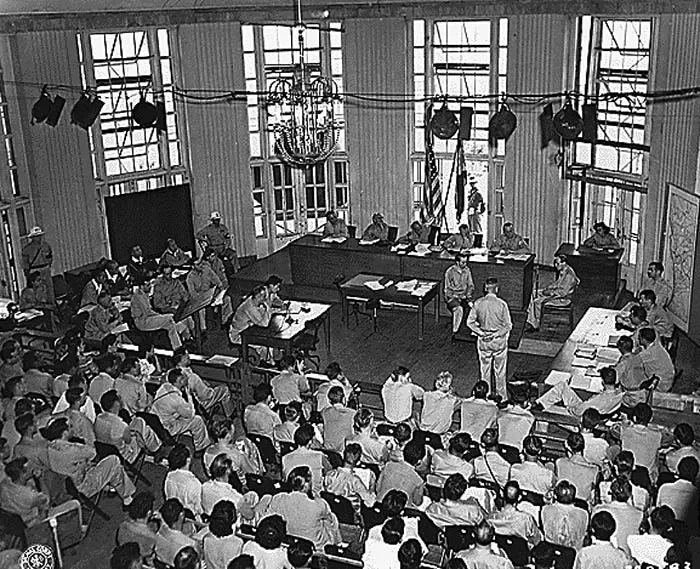

This page contains the testimony of Conchita Lualhati on Japanese atrocities committed in the town of Taal, Batangas in 1945. Lualhati also testified in the trial U.S.A. v Tomoyuki Yamashita, the transcription of which is also available at this web site. This particular transcription is from her testimony in U.S.A. v Shumpei Hagino, et. al. The pages contained herein are now declassified and were part of compiled documentation1 of war crimes trials conducted by the United States Military Commission after the conclusion of World War II. This transcription has been corrected for grammar where necessary by Batangas History, Culture and Folklore. The pagination is as it was contained in the original document for citation purposes.

[p. 24]

CONCHITA LUALHATI

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. GUTHRIE

A My name is Conchita Alas Lualhati.

Q Where did you reside during the month of February, 1945?

A We were in Batangas in a barrio named Cubamban [Cubamba].

Q Is that a part of the municipality of Taal?

A Yes, sir, it is a part of the municipality of Taal.

Q Do you recall a raid by Japanese soldiers during that month?

A Yes.

Q What date?

A It was February 16, 1945.

Q On February 16, what was the first thing you noticed about that day?

A Well, in the morning of that date, the first thing I noticed was the running of many people and shouting, saying that [the] Japanese were coming.

Q What hour of the day was that?

A It was between eight and nine in the morning.

Q Will you relate the next thing that happened?

A We were at that moment — we were in our house. When I saw that people were running, and telling that there were Japanese coming, at first I did not move, but then I heard shot after shot and then followed by [the] screaming of children.

[p. 25]

A The whole family.

Q Would you name the people and who they were, whether they were members of your family?

A Yes, they were my mother, my mother-in-law, my two sisters-in-law, my three daughters – I mean four daughters because one is still a babe, husband, the two servants, and several nephews and nieces.

Q Do you recall their names at this time?

A Of course.

Q Will you state them, please?

A Well, my mother is Vicenta Atienza. My mother-in-law, Apolonia Lualhati and my sister-in-law, Tranquilina Lualhati. There was Matea Morales, Rosio Orlina, Vicente Orlina, and Herminica. Then there were my three daughters, Ligaya, Antonia, Milagros Lualhati. There was Augusto Orlina and my husband, Jose Lualhati.

Q You reached a point in your testimony you were still in your house and had not left. Then, what did you do and what did the others do who were present?

A Then, when I heard shot after shot and [the] screaming of children and tramping of feet, we prepared to leave our place. Of course, my husband got my little babe and I got a little bag where I put some dresses of my little one and then we ran in the right direction. Now, we saw the sugarcane plantation and we decided to hide ourselves in

[p. 26]

[p. 27]

Q How old was that baby?

A One year old. The bodies were half burned because they happened to be killed in a place where it was very near a house. They were near a fence, a bamboo fence, so I saw them dead and half-burned so I could not do anything because we were all tired and hungry.

Q Could you recognize whose bodies those were?

A Yes, I was able to recognize the bodies of my husband and child. My other child was not killed, but she was shot through her right ear. Of course, it was just a little wound and she was the one who related to us that her father and the little babe were killed by the Japanese, but then I went around to look for some men to help me take the body of my husband, but what I found at a distance were some dead bodies of our tenants and some neighbors in the place.

Q What were their names?

A Some of their names, of course, I cannot remember all the names. I think there was Josefa. I only know her by the name of Josefa. There was also Antonio. I don’t know their family names because I am not from the place. I was only in that place and I, of course, was only an evacuee and, of course, I didn’t know their names but I saw about twenty of them, at least. Then, I was so helpless

[p. 28]

Q How many people, Filipino people, did you see yourself being killed that were killed in front of your eyes?

A I did not see actually because I fell in a ditch or in a deep ravine, but I could picture what the Japanese were doing at the upper direction, because after shots, you would hear the screaming, then crying, then lamenting. Of course, you could picture what they were doing there and you could see smoke all around to show that the whole barrio was in flames. All the houses were burned, not even one was spared.

Q Do you know how many people were killed in that barrio?

A Of course, I did not count them, but somebody told me that —

[p. 29]

COLONEL HAMBY: The law member will rule.

COLONEL POBLETE: The objection is sustained.

A The bodies that I actually saw, of course, when I was searching for some people, were about twenty, but some said there were some more dead bodies which might be more than fifty.

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MORRISON:

A Well, on the 15th, there was burning.

Q Were there any killings?

A No killings before that date.

MR. MORRISON: That is all.

COLONEL HAMBY: Any questions by the Commission? There appears to be none. The witness is excused.