Testimony of Juanita Barrion on Japanese Atrocities Committed in Taal, Batangas in 1945

[TRANSCRIPTION]

This page contains the testimony of Juanita Barrion on Japanese atrocities committed in the town of Taal, Batangas in 1945. The pages contained herein are now declassified and were part of compiled documentation1 of war crimes trials conducted by the United States Military Commission after the conclusion of World War II. This transcription has been corrected for grammar where necessary by Batangas History, Culture and Folklore. The pagination is as it was contained in the original document for citation purposes.

|

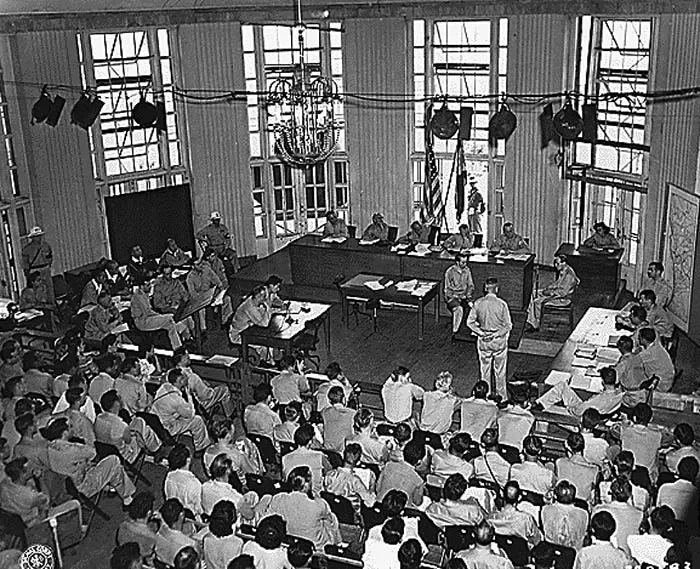

| Photo taken during the war crimes trials in Manila. Image credit: U.S. National Archives. |

[p. 1628]

JUANITA BARRION

DIRECT EXAMINATION

A My name is Juanita Barrion.

Q Where do you live?

A I live in 1125 Washington Street, Sampaloc, Manila.

Q Before you came to Manila, where did you live?

A I lived in Taal, Batangas, before we came to Manila.

Q Now, early in 1945, did you evacuate Taal to another barrio?

A Yes.

Q What barrio did you go to?

A We evacuated to the barrio of Maabud.

CAPTAIN REEL: Spell it, please.

CAPTAIN PACE: M-a-a-b-u-d.

A Yes.

Q Will you described what happened in the morning of that day, please?

A In the morning of February 16, around 10 o’clock, we heard a great commotion around us, and after having learned from the people that the Japanese were burning a neighboring barrio, we left our house running as fast as

[p. 1629]

Q How far was this ravine from Maabud?

A I don’t exactly know how far, but I know it was between Maabud and Mulauin.

Q How do you spell Mulauin?

A M-u-l-a-u-i-n.

Q That is a very short distance from Maabud?

A Yes, not far from Maabud.

Q And this ravine to which you went was between those two barrios?

A Yes.

Q How many people in addition to your family went to this ravine?

A According to my calculations, there were around 50.

Q What happened after these 50 people went to this ravine? Speak slowly, please.

A Well, we found out when we were down in the ravine that many people followed us. I can still remember that the men had their bigger children, because we women, with the little children carried to their breasts, were praying. During those moments, there was nothing but suppressed whispers. We were in such suspense that about 2 o’clock

[p. 1630]

A I can’t exactly tell because that was only due to the hand grenades. Only a few were dead.

Q What else happened there?

A Then afterwards, I heard nearer and nearer the soldiers, and then we knew that the enemy was being sent to finish us. Prayers burst from our lips and we were nervous because we knew that we were helpless and defenseless. Our escape was really hopeless. Then afterwards, I turned my head and I was confronted with the ugly mess of machine guns and then shots were fired and the swinging of blades, and many of the people fled above me, and I do not know what happened because I was wounded.

[p. 1631]

A I think around 30 people were killed.

Q How many of you escaped from the ravine, then?

A Including my family were around 17 who went up that ravine.

Q Where did you go from the ravine?

A We did not move just then from the ravine because it was impossible for us to get up. And my sister and I carried the wounded, and besides, we were afraid that the Japanese were still around. So, we waited for some help. Luckily, around 5 o’clock in the afternoon, help came. Two of our distant relatives came and saw. After taking some bamboos and a sheet that they picked somewhere, we were able to make an improvised stretcher, and we carried the wounded up the ravine. Finally, we reached a mango tree near the base of the Talang.

Q And where is this mango tree in Exhibit 243?

[p. 1632]

GENERAL REYNOLDS: Very well.

A We were 17 who reached the mango tree and mostly children. They were mostly children. Other survivors were mostly children. I think seven or eight children.

Q And what did you do after you reached the mango tree?

A Well, nothing happened. We finished carrying the wounded around 2 o’clock in the morning and daytime came and still no help, because the place was totally abandoned. I could not get any banca to carry the wounded, and the sick was unattended. My baby brother was crying. He was crying for milk. At first, I was unable to soothe him with the sugarcane juice. After a while, he didn’t like it anymore. He was crying bitterly. So, I made up my mind to get food somewhere and help for the sick. But my father opposed the idea because there was fighting still in the neighboring barrios of Pansipit and San Nicolas and Talang. But I braved it in spite of his refusal. I left carrying my baby brother with me in order to seek for food and help.

Q When did you leave for help?

A Because I —

Q When? When?

A In the morning of February 17th, around 10 o’clock.

Q What morning?

[p. 1633]

Q You testified that you went to the ravine on the 17th.

A No, I did not go to the ravine on the 17th.

Q When did you go to the ravine?

A I was there on February 16th, and then after I went for help.

Q You went to the ravine on the 16th?

A Yes, I was there.

Q And when did you leave the mango tree?

A I left the mango tree on the 17th.

Q Whom did you take with you?

A I took my baby brother with me, five years old.

Q How many did you leave at the mango tree?

A Well, we were 17; two left, and so there were 15.

Q When did you return to the mango tree?

A I came back to the mango tree six weeks afterwards.

Q And what did you find when you returned six weeks later?

A I found the sugarcane still burned and on the branches of the mango tree, I saw pieces of clothes hanging and I saw the dead bodies of my parents, my brothers and my small sisters.

Q How many dead bodies did you see there?

A I can’t say exactly how many because only small bones could be detected.

Q Approximately how many?

A I was only able to — I think I was able to get all my family and other pieces of bones. I couldn’t count, because I could not count because they were all pieces.

Q How many of your family did you get?

[p. 1634]

Q Did you go back to the ravine?

A Yes. I went that day to the ravine.

Q What did you find there?

A I found dead people.

Q About how many?

A About the number I gave you: around 30.

Q 30?

A Around 30.

limb of Consolacion Mayuga

was marked Prosecution Exhibit

No. 265 for identification.)

A I think it is Consolacion Mayuga. She was wounded.

Q What kind of wound is that, do you know?

A I don’t know.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: There being no objection, it is accepted in evidence.

for identification was re-

ceived in evidence.)

de Sagun was marked Prose-

cution Exhibit No. 266 for

identification.)

A Yes. This is Janita de Sagun. She was with us also

[p. 1635]

GENERAL REYNOLDS: There being no objection, it is accepted in evidence.

for identification was re-

ceived in evidence.)

Jr. was marked Prosecution

Exhibit No. 267 for identi-

fication.)

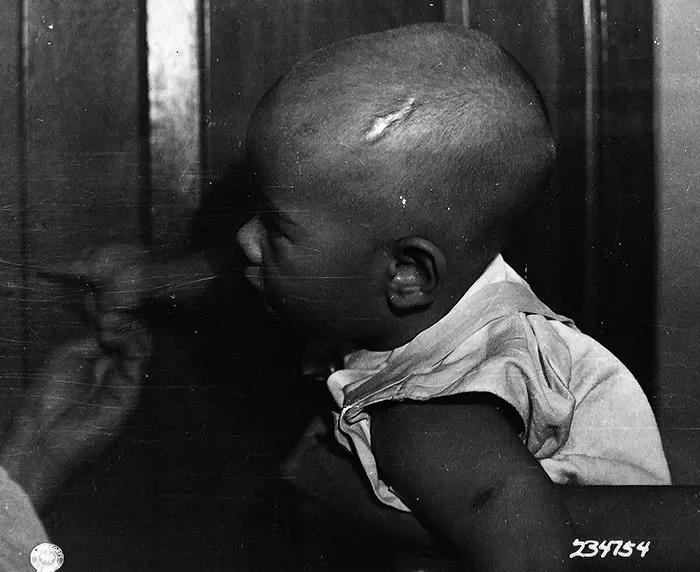

|

| Exhibit No. 267 showing Vicente Barrion with bayonet wound on head. Image credit: U.S. National Archives. |

A This is my brother, four months old, who was wounded.

Q How did he receive that wound on his head?

A Bayonet.

Q Japanese?

A Yes.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: There being no objection, it is received in evidence.

for identification was re-

ceived in evidence.)

front limb of Consolacion

Mayuga was marked Prosecu-

tion Exhibit No. 268 for

identification.)

A This is Consolacion Mayuga.

Q Does that show the wound that she received there?

[p. 1636]

GENERAL REYNOLDS: There being no objection, it is accepted in evidence.

for identification was re-

ceived in evidence.)

CROSS EXAMINATION

A Yes.

Q Can you tell us what those orders were?

A I am sorry. I don’t know any Japanese. I just know that they were Japanese words, but I can’t speak Japanese.

Q And did you hear a lot of talking by the Japanese?

A After that? After?

Q Yes, that’s right.

A Yes, they were talking.

Q Loud voices?

A Yes, loud voices.

Q But you didn’t see those Japanese?

A I saw them. They went down to the ravine.

Q Where did you see them?

A They were just a few paces from us when they set the machine gun.

Q You say you heard an explosion. Is that the first time you ever heard an explosion of that kind?

A No.

[p. 1637]

A In the early part of the morning after 10 o’clock, we heard explosions after explosions.

Q Where?

A In the vicinity.

Q Were those explosions coming from the nearby barrio?

A Nearby barrio and in the barrio itself.

Q I see. Well, were they coming from the direction of the nearby barrio where there was fighting going on?

A I don’t know. I didn’t know of any fighting.

Q Well now, what was this fighting that was going on in the nearby barrio?

A I didn’t say there was fighting. There was [a] great commotion and we heard that the Japanese were burning and killing people.

Q I want to refresh your recollection, Miss Barrion. You stated on direct examination that on the 17th, your father came to the mango tree and said, “Don’t go to the neighboring barrio because there is fighting going on there.”

A Yes.

Q Is that right?

A Yes.

Q Who was fighting whom?

A We didn’t see actually the fighting. We heard only the explosions and fighting, and of course, we could detect that they were burning.

Q Did it sound like artillery fire?

A Machine gun and hand grenade.

[p. 1638]

A No.

Q And the explosion you heard above your head, was it of the same kind that you heard from the nearby barrio?

A Yes.

Q And you say that you do not know who was fighting whom in the neighboring barrio?

A No.

Q Do you think it is possible that the fighting in the nearby barrio might have been between the Japanese and the guerrillas?

A (Nodding negatively.) I couldn’t tell because I didn’t see them.

Q Were you never curious as to who was fighting whom in the nearby barrio?

A No. I was so much engrossed with my wounds and wounds of my family that I didn’t notice. We just knew that it was fighting.

Q Do you think it possible that you people in the ravine were caught in the middle between the Japanese and the guerrilla forces?

A No. We were in complete silence when the Japanese attacked us.

Q In Taal, can you tell us whether there were any Japanese soldiers stationed?

A I don’t know of any Japanese. I had no contact with any Japanese and can’t tell you.

Q You never saw any Japanese soldiers?

A I could see them passing back and forth on the streets;

[p. 1639]

Q Well now, if I were to tell you that the total Japanese garrison in Taal amounted to eight soldiers, would that refresh your recollection?

A I didn’t even reach the garrison in Taal.

REDIRECT EXAMINATION

A I don’t know when the Americans liberated Taal because we were in the hospital at that time.

Q When was that when you were in the hospital?

A From February 20th, we were in the hospital until one month and a half afterwards.

Q Do you know what the explosion was that you heard at the ravine?

A Yes. Hand grenades.