Lemery: Historical and Folkloric Notes about some of its Barrios

This is yet another article in the series dedicated to historical and folkloric trivia about the barrios of Batangas. The information contained herein is all from documents required of the administration of President Elpidio Quirino in 1951 of all Department of Education districts around the country to help reconstruct the nation’s history down to the level of barrios. This was because many historical documents were inevitably destroyed in World War II.

Not all barrios of present-day Lemery are included. It is possible that the missing barrios may have had no documents submitted on their behalf; and if there were, these could have been destroyed by time and could not be digitized by the National Library of the Philippines, which has archived the digitized documents and made these available over the Internet. It is also possible that some present-day barrios were still part of other barrios back in 1953, when the documents were collected.

Arumahan

The name of this barrio was supposed to have been taken from the aroma tree, which farmers trying to clear the land dared not touch because of its spines. This tree is the sweet acacia, alternatively called “romas” in Tagalog1. Because the aroma was left untouched, it grew in the barrio in abundance. Although the barrio had been in existence for some time, it was only formally inaugurated as a barrio in 1880. Its original families were the Endozos, Villaloboses and Castillos.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Arumahan

|

| Aroma was supposed to have been named after the sweet acacia, also called aroma in Tagalog. Image credit: Philippine Medicinal Plants. |

Ayao-Iyao

According to folklore, the barrio’s name came from the word “ayaw” (I do not like) which one of the barrio’s beautiful ladies kept saying to her parents when they wanted her to marry their friend’s son. Rather than agree to the marriage, she ran away, all the way shouting “Ayaw! Ayaw!” [And not that this story explains the “iyao” part.] The barrio was established in 1893. Originally, the vast lands of the barrio were owned by one Octavio Garcia, whose family was the original settlers of the place.

Source: History and Cultural Life of Barrio Ayao-Iyao

Balanga

The barrio’s name was supposed to have been taken from “banga,” a large earthenware jar used for storing liquids and even milkfish fry for transport to fishponds in Rizal and Cavite. The barrio’s original settlers were the families of Andres Capuno, Graciano Toleos and Anaceto Aguila.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Balanga

|

| Balanga's name was supposed to have been taken from large jars called the "banga." Image credit: NCCA on Flickr. |

Bukal

According to folklore, this barrio’s name was given by Spaniards who were exploring the area and asked natives from where they could get a drink, and the natives pointed them at a place where there was a “bukal” or a spring. In the late nineteenth century, the barrio was frequently raided by bandits who kidnapped and murdered its inhabitants. A plague of locusts also descended upon the place, causing famine. During the Japanese occupation, the barrio’s inhabitants were forced by the invading forces to plant their fields with cotton, but otherwise left them unharmed.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Bukal

Cahilan

In 1953, Cahilan was still one big barrio, subsequently divided into Cahilan I and II. The barrio’s name was supposed to have been taken from a fruit tree of the named cahil. I am, however, unable to find any references about this fruit over the Internet. The barrio was established in 1891. Originally, a large section of the barrio was owned by the family of one Ciriaco Caguicla. Over time, however, other families were able to buy parcels of land from him so that the land was eventually settled.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Cahilan

Dayapan

According to folklore, the barrio used to be heavily forested until settlers arrived to clear the woods. They began planting new trees including a variety of lemon called the “dayap,” from which the barrio’s name would be taken. Other settlers arrived and like the original ones also planted dayap trees, until people started to refer to the place as “dayapan,” roughly “the place where the dayap grew” or “was grown.”

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Dayapan

Gulod

This barrio’s name was supposed to have been given because it was descriptive of its topography, the Tagalog word “gulod” meaning a hilly place. The barrio itself was supposed to have been established in the middle part of the nineteenth century. The barrio’s original settlers were the families of Felix Martinez, Martin Catapang, Basillo Villalobos and one “Kabisang” (cabeza or head) Pedro. According to the town’s elders back in the early fifties, there used to live in the barrio two brothers who were heads of groups of “tulisanes” or brigands, which robbed the houses of rich folks as far as San Juan de Bocboc (as the town of San Juan used to be known).

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Gulod

Malinis

According to folklore, the Spaniards gave the barrio its name after having noticed that its inhabitants traditionally kept the neighborhood clean, planted flower gardens and built toilets without having to ask for these from the government. In 1896, many of the barrio’s inhabitants had to flee persecution by Spanish soldiers, presumably after the Philippine Revolution2 had erupted. The evacuation happened again during the Japanese occupation, when the barrio’s inhabitants had to leave because of the cruelty of the invading army’s soldiers.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Malinis

Masalisi

Before the arrival of the Spaniards, the barrio used to be heavily forested. One day, an old couple arrived searching for another barrio. Because of the difficulties that they encountered, they were supposed to have repented, or “nagsisi” in Tagalog, and it was from this incident that the barrio got its name. [This folkloric story has too many loose ends, but that was what the reference document said; hardly an explanation at all.] The barrio was established in the year 1892, and its original settlers were the family of one Maria de Cabahog, who owned most of the barrio’s lands. The family was kindhearted and would eventually sell parcels of lands so that other settlers would come to populate the barrio.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Masalisi

Mataasnabayan

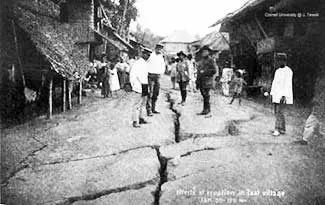

According to folklore, Mataasnabayan was originally a site chosen by the Spaniards for the setting up of a pueblo or a missionary community, but abandoned it because of the difficulty of trading with other villages and the difficulty of obtaining water. The barrio’s name, therefore, was given because of its topography, literally meaning upland. The barrio’s original settlers were the Ricalde, Magsino, Marquinez and Vito families. During the 1911 eruption of Taal Volcano, part of the barrio’s land was supposed to have sunk from the preceding seismic activity. During the Philippine Revolution, Filipino freedom fighters found refuge in Mataasnabayan because it was upland and away from the town centers, until the Spaniards discovered this and turned the barrio into a military zone.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Mataasnabayan

|

| Seismic activity related to the 1911 eruption of Taal Volcano was said to have altered the topography of Mataasnabayan. Photo from John Tewell's collection on Flickr. |

Matingain

Presently Matingain I and II, in the early fifties these two were just one barrio. The name was supposed to have been given because this was where “tingga” or lead used to be found. This was used by fishermen to weight down their nets. If this was the case, then the barrio’s name is misspelled and should instead be Matinggain.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Matingain

Nonong Casto

According to folklore, before the Spaniards arrived in the Philippines, the barrio used to be a forested area through which a brook ran. From this brook, people fished for crabs and shrimps. Many people were said to have died in the brook, their deaths attributed to a “nuno,” a folkloric elfin creature. When an old man who went by the name of Kasto or Casto went there to fish for crabs and subsequently died, the place was named after him.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Nonong Casto

Payapa

In the fifties, Payapang Ibaba and Payapang Ilaya used to be just one barrio. Its old name was Tabla, after the wooden house built by a Spanish priest from Taal named Fr. de la Rosa who had sought refuge in the place. The name was subsequently changed to Payapa, after the balete tree which is alternatively known by the same name. The barrio was said to have been founded in 1891. Its land were said to have been originally owned by one Pedro Obrador and his family. The family, while wealthy, eventually had to sell off parcels of their land, paving the way for other people to settle the barrio. Although a small barrio, Payapa was among many which revolted against the Spaniards, its people led by one Capitan Miguel and Julian Montalban.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Payapa

|

| Payapa was said to have been named after the balete tree, alternatively called the payapa. Image credit: Choose Philippines. |

Sinisian

According to folklore, natives of the barrio overheard Spanish soldiers who had just been defeated by the American Army talking to each other, and all they could understand was “Si! Si!” (Yes! Yes!) For some strange reason, the natives thought that the Spaniards were blaming each other for their defeat. Soon came along American soldiers who were looking for a drink, and asked the natives for directions to a spring where the Spaniards had earlier rested. The natives pointed them towards the place where the Spaniards were “nagsisisihan” (blaming each other), so the Americans thought Sisihan was the name of the place. The barrio itself was said to have been established in 1896. Sinisian was said to have been originally owned by the family of one Agueda Reyes, which then sold parcels of land to other would-be settlers of the barrio.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Sinisihan

Talaga

It was said that Talaga used to be one of the richest barrios in Lemery; and that its name was taken from a spring in the barrio from which people drew water for their everyday needs. The barrio was supposed to have been established in 1918 and was initially settled by eleven families. During the Philippine Revolution, members of the Katipunan were said to have hidden in the barrio because it was not very accessible. The Spaniards, however, heard of this and burned all the houses in the barrio. In World War II, Talaga again served as a place for war refugees because of its inaccessibility, which kept it insulated against the atrocities committed by the Japanese soldiers.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Talaga

Tubigan

According to folklore, this barrio’s name was supposed to have meant “little sea,” as it served as something of an extension to Balayan Bay. The waters that flowed towards it were thought to have originated from Barrio Bukal. In time, though, enough soil was deposited on it, presumably by the flowing water, so that vegetation would arrive. This barrio was formally established in 1860 and its original settlers were the de Castros, Patotos and the Caguiclas. During the Philippine Revolution, the Spanish Guardia Civil raided houses in the barrio in search of contraband, the set the houses on fire. During World War II, conflicts between the Japanese soldiers and Filipino guerrillas were settled amicably through the efforts of one “Teniente” Caag, so that the barrio was more or less left in peace.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Tubigan

Tubuan

This barrio’s name was supposed to have originally been “Tubuhan,” or where the sugarcane was planted. In the beginning, it had no permanent settlers but instead it was cleared by “kaingin” by farmers who would leave as soon as the crops were harvested. In time, permanent settlers arrived and would turn to planting the fields with sugarcane. The place formally became a barrio in 1902. Its original permanent settlers were the families of Mariano Villalobos, Francisco Galit and Leon Catapang. During World War II, inhabitants of the barrio would be subjected to the atrocities that the Japanese became known for. Men, women and children would be tortured and during investigations, presumably for guerrilla movements.

Source: History and Cultural Life of the Barrio of Tubuan

|

| Tubuan was so named supposedly because its fields were planted to sugarcane. Image credit: University of Michigan Digital Collections. |

2 The Philippine Revolution erupted in August of 1896. Wikipedia.