10 More Batangas Historical Trivia Likely Unknown Even to Batangueños

[In this article: Batangas City Batangas, Nasugbu Batangas, Tuy, Bataangas, Lipa City Batangas, Agoncillo Batangas, San Luis Batangas, Taal Lake, Taal Volcano, wheat growing Batangas, Lemery Batangas, San Geronimo Lemery]

A few months back, Batangas History ran a piece containing otherwise forgotten historical trivia about the Province of Batangas. The piece was aimed at readers who do not have the patience to go through lengthy historical discourses. This article is a continuation of that earlier piece and contains snippets of information about Batangas that are otherwise forgotten.

The pieces of trivia are contained in subsections for the readers’ convenience and provided citations with links to source documents whenever possible for anyone who wishes to follow through with additional readings.

|

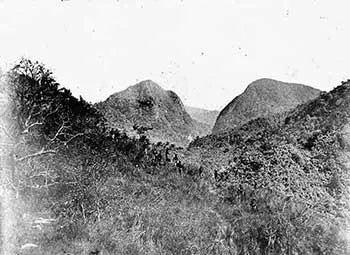

| In the absence of roads, American soldiers had to hike over mountains during the Fil-Am War. Image source: Fort Worth Library. |

1. There were no roads from Magallanes, Cavite to Nasugbu in 1900

As close as the Municipality of Magallanes in Cavite is to Nasugbu – the distance is roughly 17 kilometers as the crow flies1 - getting from one town to the other meant a hike of up to three days early in the 20th century because there were no roads for wheeled horse-drawn vehicles. In 1900, soldiers of the United States Volunteers’ 28th Infantry Regiment who were marching to Nasugbu had to go “over the passes and ravines of the Alfonso range of mountains and through perilous defiles2 that could have been held by almost a squad of insurgents…3”

2. The town of Agoncillo was first called Pansipit

The present-day town of Agoncillo was originally part of Lemery. In 1945, a committee within the local government of Lemery proposed the separation of 11 of the town’s barrios to form a separate town that would be called Pansipit. The proposal was endorsed to the Secretary of the Interior and subsequently approved, with then-President Elpidio Quirino signing Executive Order No. 140 creating Pansipit. The municipal council of Lemery, however, filed a counter-resolution asking for the revocation of the order until a plebiscite could be held to determine the pulse of the people living in the said barrios. The plebiscite done, with the people of the barrios voting for separation, in 1949 Quirino signed Executive Order No. 212 creating the new town but not as Pansipit but as Agoncillo in honor of Don Felipe Agoncillo, remembered in history as the first Filipino diplomat4.

3. Lipa was the only town mentioned in the Declaration of Independence

But this piece of trivia, it has to be said, has to be seen in the right context. The Province of Batangas was mentioned twice in the 1898 Philippine Declaration of Independence from Spanish rule, first as among the provinces to which the revolution “spread like wildfire;” and second, to explain that it was represented in the new nation’s flag as one of the eight rays of the sun. The mention of Lipa was as one of the towns where “resistance of the Spanish forces was localized” – along with San Fernando, Macabebe, Sexmoan, Guagua, Calumpit, among others – after the Filipino revolutionaries had rid other towns – mostly in Luzon – of their presence5.

The present-day town of San Luis was originally a barrio of Taal called Balibago, so called supposedly because of its nearness to the Balibago River6. The barrio’s inhabitants in the 19th century clamored to become a distinct town, and their wishes were granted when Balibago was declared a municipality to be called San Luis in 1861. In 1904, however, because of its low income, the new American colonial government reintegrated the town back into Taal as a barrio. Prominent citizens continued to lobby for separation from Taal and their efforts were rewarded when San Luis was declared a distinct municipality on the 2nd of February 19187.

5. There are sunken ruins underneath Taal Lake

The 1754 prolonged eruption of Taal Volcano released enough volcanic debris into the atmosphere to close off an erstwhile channel connecting what is now a freshwater lake to Balayan Bay. Over time, the lake’s water would start to rise, inundating the earliest lakeside towns of Taal, Lipa, Tanauan and Sala. Inhabitants of these towns, wrote researchers Thomas Hargrove and Isagani Medina in a 1988 paper8, “fled their submerging towns” and resettled in safer places. The two researchers wrote of having seen ruins while snorkeling off barrio Lumang Lipa (presently part of Mataasnakahoy), “Parallel rows of wall-like structures, one to two meters high, rose from the lake bottom… Some walls were vertical and straight, othcrs wcre crumbled… The wall looked man-made.”

6. Wheat used to be grown in Lipa

Contrary to popular belief that wheat can be grown only in temperate countries, this grain crop can actually be raised in the tropics as well, including the Philippines. In fact, there are historical records of of it being grown in the country. Wrote C. R. Escano in an abstract to a 1985 paper, “Wheat production in the Philippines has some remote antecedents during the Spanish regime, but has totally disappeared recently9.” Even after the end of Spanish rule and the start of the American colonial era, wheat continued to be grown in the country. Lipa, according to a 1905 publication of the Bureau of Labor, was one town where it was. “Irish potatoes can be raised in the north Luzon highlands, and in the early days wheat enough to supply the Manila market was raised around Lipa, in Batangas province10.”

7. Tuy was burned twice by opposing forces during the revolution

The western Batangas town of Tuy was burned at least twice by opposing forces during the Philippine Revolution against Spanish colonial rule. In September of 1896, Filipino revolutionaries attacked and captured the town, forcing inhabitants to evacuate. When Spanish forces arrived from the garrison in Balayan, the rebels fled but not before setting fire to “the church, the municipal building and all houses in the town11.” The following year, in October of 1897, the rebels “mustered sufficiently to attack Tuy.” To this, the Spanish response was to burn the town as they did in Calaca, Taal and Balayan12.

8. There were 17 schools in Batangas in 1901

According to a Captain Peed of the 32nd Infantry Regiment of the United States Volunteers, there were just 17 schools in the Province of Batangas that he had been able to identify by March of 1901. There were just 22 “native” or Filipino teachers attending to the needs of 2,273 students. This figure was far outnumbered by those not in school, a total of 3,441 children. The average daily attendance was a mere 67. Not surprising because the American colonial era in the Philippines was still in its infancy, there were only 3 English teachers throughout the entire province13.

9. The Batangas pier and Barrio Sta. Clara were ordered destroyed in 1941

On the 24th of December 1941, already fidgety because of the impending invasion by the Japanese, the United States Army executed an order from high command for the destruction of the pier at what was then Batangas Town. This move was in reaction to an intelligence report that Japanese warships were planning to land on the shores of the town. The pier was demolished using powerful explosives, resulting in conflagration in the community along the shoreline. “Almost all the houses in Santa Clara were burned,” said the researchers for the so-called “historical data” for Batangas Town. Furthermore, a few days later, authorities ordered the burning of all lumber and hardware stores in Santa Clara to prevent the Japanese from benefitting from these14.

|

| The pier at Sta. Clara had to be demolished in 1941 so the US Army had to construct a new one after liberation in 1945. Image source: United States National Archives. |

10. 20 men in Lemery attacked a Spanish garrison in 1840

Although the Philippine Revolution against Spanish colonial rule would not break out until 1896, as early as the first half of the 19th century there were already stirrings if not necessarily of nationalist fervor then certainly of discontent with the church-dominated Spanish rule. After disgruntled locals in the town of Lemery had kidnapped a priest and his sacristan, in 1839 the Spanish Guardia Civil retaliated by committing atrocities and vandalizing the properties of the town’s inhabitants. Daily executions were carried – likely to get to the bottom of the kidnapping – out with little consideration for actual guilt. By 1840, when the inhabitants of Lemery – still known as San Geronimo at the time – could no longer bear the injustice, they hatched a plot to send 20 of the town’s bravest men to undertake a clandestine attack on the Spanish garrison. The attack ultimately failed and all 20 men were supposed to have been killed15. Seen in the light of a bigger context, however, the failed attack was just one of the signs that the Spanish colonial government failed to heed of what it would face later that same century.

Notes and references:

1 As measured on Google Earth.2 A “defile” is a narrow pass or gorge between mountains or hills. Wikipedia.

3 “In Memoriam; C. Rodman Jones, Born Aug. 14, 1875, Died June 25,1909,” by Charles Henry Jones, published 1908 in the USA.

4 “Executive Order No. 212, s. 1949,” online at the Philippine Gazette.

5 “Philippine Declaration of Independence,” Wikipedia.

6 “Origin of San Luis,” online at the San Luis LGU Official Web Site.

7 “Historical Data of San Luis Batangas,” online at the National Library of the Philippines Digital Collections.

8 “Sunken Ruins in Taal Lake: An Investigation of a Legend,” published 1988 by Thomas Hargrove and Isagani Medina in the Philippine Studies journal of Ateneo de Manila University.

9 “Abstract: Wheat growing in the Philippines [1985],” online at the Food and Agriculture Organization.

10 “Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor: No. 58,” published May 1905 by the Government Printing Office, Washington D.C.

11 “Historical Data of the Municipality of Tuy,” online at the National Library of the Philippines Digital Collections.

12 “Remarks Upon the Statistical Tables of the Towns of Taal, Tuy and Calatagan – Showing Results of Benevolent Assimilation,” by James A. LeRoy, part of “The Calamities of Balayan, P.I.: Reply to a Criticism of a Petition Made to the Taft Expedition of 1905, by the Petitioners,” published 1907 in Boston, Massachusetts.

13 “Annual Report of Major General Arthur MacArthur, U.S. Army, Commanding, Division of the Philippines, Military Governor in the Philippine Islands Volume II,” published 1901 in Manila.

14 “History and Cultural Life of the Poblacion Batangas,” online at the National Library of the Philippines Digital Collections.

15 “Historical Data of Lemery,” online at the National Library of the Philippines Digital Collections.