The Glory of 19th Century Villa de Lipa as Described by a Spanish Historian

A nineteenth century book written by the Spanish ex-government official and historian Manuel Sastron1 painted a captivating descriptive picture of Batangas during the era, including the glory years of Villa de Lipa, to which an entire chapter was dedicated. This article attempts to condense what Sastron wrote to perpetuate memories of an era which can alternatively be thought of as the City of Lipa’s first golden years.

Just to make sure all readers are on the same page, in 1887, the same year that coffee production in the erstwhile town of Lipa reached its peak, Spain’s Queen Regent Maria Cristina issued a royal decree which bestowed upon the town the title “Villa de Lipa,” effectively elevating it into a city because of its income. The title was revoked in 1895 after the coffee bubble burst, and Lipa reverted back to being a town2.

Naturally, Lipa in the nineteenth century was far different from what it has become today, although there are a few things that have not changed. Sastron wrote that the town was connected to the then-town of Batangas by way of a main highway that also goes all the way to Laguna and Manila. There were also roads, likely the same in the present day, that connected Lipa to Rosario, Ibaan and Tanauan. These were in poor repair, he noted, especially during the rainy season.

The climate was mild if humid, Sastron noted, and this was conducive to malarial fevers during the rainy season. As all of us in the present day already know, no great rivers cut through Lipa, although there were streams with their estuaries in “San Luca, Malidlid, Tangob, Pinagtong-olan and Palsam3.” There were “abundant and good waters from a spring that flows into the foot of the Mararayap4” which Sastron noted could be harnessed for irrigating agricultural fields.

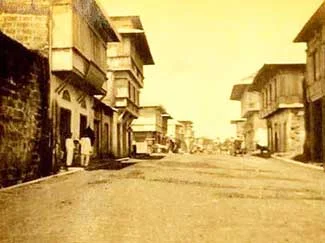

|

| Street scene in Lipa, Batangas, the rich coffee town of former days. Image credit: Luther Parker Collection of the National Library of the Philippines Digital Collections. |

Large swathes of land were thickly forested and from which could be hunted deer, wild boars, goats, wild cats and even “harmful animals.” Many of these forested lands, however, had been converted into coffee plantations.

Villa de Lipa’s population was pegged at “40,000 souls.” It had 46 barrios in all (as opposed to 72 barangays in the present day). Of these, the most important for Lipa’s growth and wealth were “Mataasnacahoy, Sapar, Payapa, Luta, San Gallo, Mataasnalupa, Talisay, Sabang, Pangao and Lumbang5.”

It was coffee that transformed the town’s fortunes. According to Sastron, the first coffee plants were planted in Lipa “around the year 1814” through the initiative of the Gobernadorcillo6 Galo de los Reyes and the Augustinian religious Brother Elias Lebredo. Production of coffee would peak in 1887 with a one-time harvest of 70,000 picos7.

The coffee boom brought great affluence to the families of Lipa. The houses along the main street were all built using strong materials. Up to a dozen of the town’s oldest families became exceptionally wealthy from the boon that coffee brought. These families were not only wealthy but among the most “enlightened” in the country in the sense that they were not only as sophisticated as those of their same class in Europe but had also used their knowledge to better the running of their town.

Hospitality was a trait of the nineteenth century Lipeño so that entertainment was always being organized for guests by the town’s families: a charity event, perhaps; a tour of the volcano island; a horse race; or the festive dances called “bailes.”

|

| Coffee transformed Lipa's fortunes. Image credit: U.S. National Archives; University of Wisconsin Digital Collections. |

These bailes were elaborate events for which participants spent time to rehearse. The people of Lipa were never far behind in learning the current dance crazes in Europe, be it the waltz, the rigodon or the minuet. A baile was also an opportunity for the women to wear their best fineries and jewelries. Sastron noted that it was in Lipa where he saw not just the most number of jewelries but also the most valuable.

Tables during these events were adorned with the finest silverware and ceramics; and of course food of the highest culinary standard was served and washed down with expensive Spanish and other European wines. Sastron felt torn between being thankful for the opportunity to attend these bailes and rueful for the great expenses they must have cost their hosts.

The horse races were no small matter, either; and horse owners boasted Arab and Australian breeds. Sastron noted that these were superior to those he had seen in Manila, the capital of the archipelago.

Education was among the benefits that Lipa gave to its people. Large and well-maintained public elementary schools had been built. There were also “colleges where the first three years of secondary education” were taught. However, Sastron noted that these schools were not really well-attended, the problem being that the town center was difficult to reach for young people in villages outside of it.

Lipa had its own Court of First Instance, which had jurisdiction over eight neighboring towns. Curiously, Sastron noted, there was no jail in Lipa itself; albeit this will sound less ironic when one considers that criminality in the town was insignificant.

These “insignificant” crime statistics, it has to be said, did not however include the theft of animals, which was considerably higher. This is probably not surprising because in Lipa then, where were 5,000 heads of cattle; 6,000 to 7,000 pomegranate horses; and more than 2,000 carabaos – and these were just the ones that were registered.

The peak year of 1877 was as good as it got for Lipa’s erstwhile booming coffee industry, and Sastron attributed the industry’s decline to destruction of the plants by a worm called the “bayongbong8.” At the time Sastron was writing his book – before 1895 – coffee production had declined to “almost nil.” Coffee plantations were being planted with alternative crops, with more lands being planted to sugarcane with each passing year.

The decline of Lipa’s economic might was swift, something that was felt not just in the city but also elsewhere. Sastron noted that it was most certainly painful as well to the jewelers of Manila, presumably because their most valued customers were from there. By 1895, Lipa’s city status by revoked by the Spanish crown and it returned to being a municipality.

2 “Demythologizing the History of Coffee in Lipa, Batangas in the XIX Century,” a dissertation written by Maria Rita Isabel Santos Castro, 2003.

3 Malidlid is presently called Malitlit. I am unable to determine what Palsam is in the present day.

4 Mararayap is presently called Malarayat, part of the Mount Malepunyo mountain range.

5 Payapa and Luta are presently part of the town of Malvar. I am unable to determine what San Gallo is in the present day.

6 The “gobernadorcillo” would be the equivalent of the present day town or city mayor.

7 A “pico” being a Spanish unit of measurement.

8 In her already cited dissertation2, Castro noted that the decline of the coffee industry in Lipa was due to a fungus outbreak.