19th Century Tulisanes Banditry in Calaca, Batangas

I was amused last week to hear President Rodrigo Duterte brand Senator Antonio Trillanes IV as a tulisan. I doubt that many among the younger generations even know what a tulisan is, let alone visualize what one looks like. Those of my generation, on the other hand, grew up to a steady fare of afternoon black and white movies on television which had tulisanes as the perennial villains.

But what, exactly, is a tulisan? The word has even made it to Merriam-Webster where it is defined as a “ladrone,” i.e. a thief. Its etymology is uncertain, even if there is a similar word in Bahasa Indonesia which means “writing.1” Its Austronesian root, “tulis,” has the same meaning as in Tagalog, i.e. sharp.

How tulisan came to be known as thief, bandit, brigand or highway robber is unknown, but its propagation seems to have been the work of the Spaniards in the Philippines. The word is included in the eighteenth century book “Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala” and is defined as “malhechor, salteador; de tulis, agudo.2” (malefactor or criminal, a highway man3 or highway robber; from tulis, meaning acute or sharp)

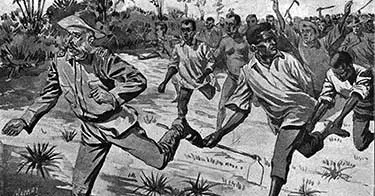

Within the context of the nineteenth century, the “malhechor” was “one who commits any transgression of law, and especially one who commits and offense habitually; and a highwayman or a thief who forms part of a gang.4” In other words, the tulisanes were not dissimilar to the horse-riding gangs of wild west movies of old which hijacked road travelers or even trains.

While bands of tulisanes abounded in the entire island of Luzon and even as far south as the Visayas, tulisan activities were apparently most common in the province of Cavite. The entire province, according to Isagani R. Medina, was known during the latter years of the Spanish colonial era as “La Madre de los Ladrones4” (The Mother of the Thieves/Bandits) This is not to denigrate the province of Cavite, however; and indeed Medina noted that many tulisan activities were symptomatic of peasant class unrest and directed towards lands seized from them by Spanish friars.

Nonetheless, tulisanes activities could be gruesome. According to Greg Bankoff, they “infested the roads and rivers, ravaged fields and farms, sacked towns, pillaged churches and set light to houses in an orgy of murder, robbery and rapine in which there was ‘hardly an evil deed that their rash boldness did not perform.’ 5“

One such tulisan raid on the town of Calaca in the nineteenth century is documented, probably from stories told by the town’s elders.6 On 5 March 1891, a band of tulisans descended upon Calaca from Cavite. The bandits were led by one Espiridion Socorro, an escaped convict who had been in hiding in the neighboring mountains to escape the jail term imposed by former gobernadorcillo Claudio Vizconde.

Socorro was actually a native of Calaca who had likely joined up with one of the many groups of tulisanes that abounded in the nearby province of Cavite. The attack on his hometown was being seen as an act of revenge.

The tulisanes did not have easy passage into the town, however. Citizens came out to defend Calaca in a two-hour battle which came to an end only when they ran out of ammunition. It was only then that the invaders gained access into the town. They went to the tribunal and robbed the town’s treasury. Done, they moved on to the house of the town’s richest man, one Ruperto de Leon.

It was after they had forced the doors of de Leon’s house open that word reached Socorro and his gang, likely from a lookout, that the Guardia Civil were on their way from the seashore. The tulisanes then beat a hasty retreat northwards, taking with them men and women whom they had tied up as hostages.

The Guardia Civil, led by one Judge Sementera Marcos, and the town’s citizens pursued them, however; and in the ensuing encounter, many of the tulisanes were killed. Among the citizens who joined the pursuit of the bandits were a Captain Apolonio Admana and one Lieutenant Mariano Admana. Both were members of the rural guards called “cuadrillos.7”

One prominent citizen who defended the town against the tulisanes was an Eleuterio Marasigan, who would become a Brigadier General in revolutionary army against the Spanish colonial rule. Marasigan fought the bandits with only a revolver but was forced to seek refuge in the cemetery when his bullets ran out.

Fortuitously, there were no fatalities among the townsfolk, Guardia Civil and cuadrilleros during the raid. Even the hostages whom the tulisanes had bound managed to untie themselves and flee to safety once the firefight between the bandits and the pursuers began. There were those among the townsfolk who thought they saw a little boy by the side of the Calaca’s defenders at the height of the tulisanes attack, and believed that the boy was the Saint Raphael, the town’s patron saint.

2 “Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala,” by Juan de Noceda, Pablo Clain and Pedro de Sanlucar. First published 1754.

3 “Tulisanes: San Mateo and Banditry,” by Joseph Scalice, online at JosephScalice.com.

4 “La Madre de los Ladrones: Tulisanismo in Cavite in the Nineteenth Century,” by Isagani R. Medina.

5 “Bandits, Banditry and Landscapes of Crime in the Nineteenth-Century Philippines,” by Greg Bankoff, online at Questia.

6 “History and Cultural Life of the Town of Calaca and its Barrios,” by the Calaca Elementary School, submitted to the Division of Balayan. 1953.

7 “Cuadrillos,” definition from the Facebook page Filipinas Nostalgia.