Testimony of Gliceria Malvecino on Japanese Atrocities Committed in Sto. Tomas, Batangas in 1945

[TRANSCRIPTION]

This page contains the testimony of Gliceria Meer Malvecino of Santo Tomas, Batangas on atrocities committed by the Japanese in the town in 1945. The pages contained herein are now declassified and were part of compiled documentation1 of war crimes trials conducted by the United States Military Commission after the conclusion of World War II. This transcription has been corrected for grammar where necessary by Batangas History, Culture and Folklore. The pagination is as it was contained in the original document for citation purposes.

|

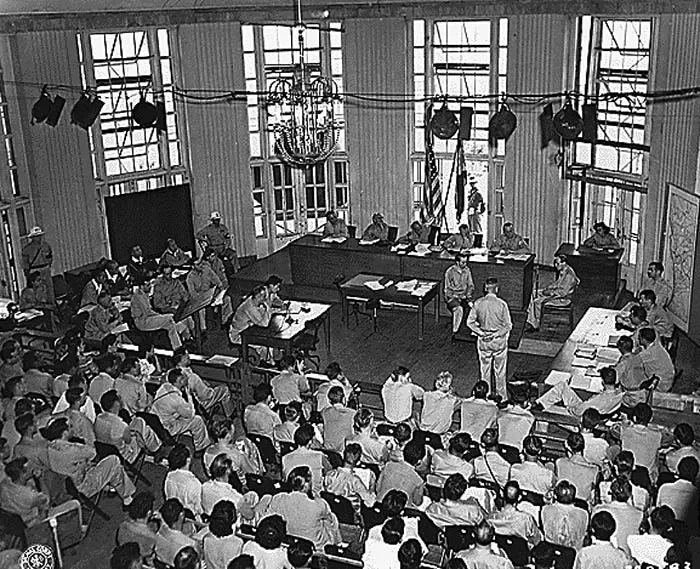

| Photo taken during the war crimes trials in Manila. Image credit: U.S. National Archives. |

[p. 1799]

GLICERIA MEER MALVECINO

DIRECT EXAMINATION

A My name?

Q Yes; state your name.

A My name is Gliceria Meer Malvecino.

Q And how old are you?

A I am 41 years of age.

Q Your nationality? You are a Filipino?

A Yes.

Q What is your address?

A Santo Tomas, Batangas.

Q On 11 February 1945, where were you?

A I was at home.

Q Where is your home?

A In Santo Tomas; the town of Santo Tomas, Batangas.

Q The Province of Batangas?

[p. 1800]

Q At about six o’clock in the morning, what were you doing?

A I heard a noise, and when I looked out of the window, I saw the Japanese soldiers, two of them.

Q Where were you?

A I was preparing my food for our breakfast.

Q Were you at home?

A Yes, sir.

Q Did anything unusual happen that morning?

A That morning, I heard a noise, and then when I [had] seen —

Q What morning was that noise?

A I don’t know what morning.

Q Well, what was that noise?

A I don’t know what the noise was. I looked out of the window, and when I looked out of the window, I saw the Japanese disorder, and they were talking some words, but those words I did not know, but the motions were made, and I understood that I should go down, and then, when we were down —

Q Just a minute, please. By the motion of whom did you understand you had to go down?

A By the motion of the Japanese soldiers.

Q How many Japanese soldiers were there that made the motion?

A Only two.

Q What did they tell you?

A I don’t know what they were saying.

Q Were they shouting?

[p. 1801]

Q Where they calling you?

A They were doing motions, but they were speaking, but we didn’t know what they were saying.

Q How many persons were in your house at that time?

A During that time, we were 16.

A We went down.

Q You came down?

A Yes.

Q What did you do downstairs?

A Then, the Japanese soldiers told us to march to the village and we went to the house of Anselma Malcaman; we were marched by two guards.

Q You say the Japanese ordered you to go to the house of someone?

A Yes; Anselma Malcaman. They did not say the name of Anselma Malcaman, but they said go there, and they made the motion to the house of Anselma Malcaman. I knew when I reached there the name of that house; I knew the owner of that house was Anselma Malcaman.

Q How far was the house of Anselma Malcaman from your house?

[p. 1802]

Q When you arrived at the house of Anselma Malcaman, were there other people there besides your group?

A Yes, sir.

Q How many were there?

A There were more, but not less, that 50.

Q Were you acquainted with the people there?

A When we reached there, I knew them, but I did not go around to see everyone.

Q What part of the house were you in?

A Downstairs.

Q What did the Japanese do with you while you were in the house of Anselma Malcaman?

A The Japanese were tying persons up, and I do not know where they were bringing them, but there were five persons tied together that they were tying like this (illustrating), and then there were five more.

MAJOR OPINION: I would like to have the testimony and the answers of the witness translated into English by an official interpreter, if it may please the Court.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: Very well.

THE WITNESS: They tied them up; The Japanese soldiers were tying them up.

MAJOR OPINION: Just one second.

(Whereupon Interpreters Lavengco and Gojunco were called to interpret the witness’ testimony).

A (Through the Interpreter) Five persons were tied, five civilians; to one rope, there were five persons tied

[p. 1803]

Q How many Japanese tied each group of five persons?

A I did not count, and I did not send anybody to count, but in my estimation, there were 50 only.

Q Fifty Japanese soldiers? I am asking you how many Japanese tied the civilians. How many Japanese soldiers tied the civilians.

A I saw eight.

Q Now, when you went into the house of Anselma Malcaman, were there both males and females that were tied into different or separate groups?

A No, sir, there were no men. There were males, but small children.

Q You mean to say that in the house of Anselma Malcaman, there were only females and small children?

A Yes. I just stayed around because I had children in front of me. I had five children around me, and I was tied.

Q Once you had been tied by the Japanese, what did they do with you?

A We were taken by the river down the slope. We were taken down the river, down a slope.

[p. 1804]

A (Through the Interpreter) While standing down-slope at the river, I saw my son —

THE WITNESS: No, my daughter.

INTERPRETER LAVENGCO: “I saw my daughter and the Japanese holding the bayonet about to strike her.”

A (Through the Interpreter) Like this, sir (demonstrating), holding with the right arm.

INTERPRETER LAVENGCO: “And I was — my eyes were covered.”

A (Through the Interpreter) The back part, lower part of my dress was torn and my eyes were covered with it.

Q Now, will you please straighten this out? You said that your daughter was held by the Japanese, and what did the Japanese do with her, if the Japanese did anything, after she was held by the Japanese in the way you have described?

A (Through the Interpreter) She was bayoneted.

Q Bayoneted. Did you see what part of her body was bayoneted by the Japanese?

[p. 1805]

Q How far were you away from your daughter when she was bayoneted by the Japanese?

Q (By Major Opinion) About what time was that, more or less?

A (Through the Interpreter) I cannot tell the time exactly, because we were taken by surprise. About 10 o’clock.

Q In the morning?

A (Through the Interpreter) In the morning.

A (Through the Interpreter) After blindfolding me, my children used to hold tight my dress, were bayoneted, including my child who was — who I was holding fast in my arm (demonstrating).

Q What was the age of that child of yours you were holding in your arms?

A (Through the Interpreter) One year, sir.

Q What was the name of that boy?

A (Through the Interpreter) Rafaelita Malvecino.

Q Was it a daughter or a boy?

A (Through the Interpreter) A daughter, and I also

[p. 1806]

THE WITNESS: I was holding a girl tied, not a boy tied. I did not tell you that.

(The witness answered again to the interpreter.)

INTERPRETER LAVENGCO: “I was holding a boy tied, not girl.”

GENERAL REYNOLDS: The Commission interrupts to ask if we wouldn’t get better results to let the witness testify in English. She seems to speak quite well in English.

MAJOR OPINION: But those cases if she cannot express herself, I would like to suggest —

GENERAL REYNOLDS: If the witness desires to speak in Tagalog, she may do so.

MAJOR OPINION: You may speak in English now.

(Translated to the witness by Interpreter Lavengco.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: The Commission has already ruled. She will just speak directly.

Please answer in English now.

(The following answers of the witness were given in English, except where otherwise noted.)

THE WITNESS: What happened?

A We fell down, and also my two small —

Q Just a minute, please. By parts, what happened with

[p. 1807]

A I fell down, and my child was crying, and then after a while, I heard no crying anymore. It seemed to me that —

Q Please. Did you see your daughter Rafaelita bayoneted by the Japanese or not?

A I did no see, because I — Q Did you know afterwards whether she was bayoneted or not?

A Afterwards?

Q Yes.

A I fell, I heard only with my ears, I could not see because I was blindfolded.

Q You were blindfolded. Now, then what happened with you after that?

A I fell down, it seemed to me that I fell down, and I heard also the cries of my two small boys.

Q What were the names?

A Vergilio Malvecino, nine years of age, and Antonio Malvecino, five years of age.

Q Where were those two boys?

A With me.

Q Where were they?

A They were with me.

Q When you fell down, where were those two boys?

A Near me.

Q Did you see them bayoneted by the Japanese?

A I did not see, but I heard only that they were shouting and crying, “Mother! Mother!”

[p. 1808]

A Then, afterwards, it seemed to me that I fell asleep; I did not know anything. Then —

Q You mean to say that you lost your consciousness?

A I lost my — (pause)

Q Consciousness?

A Yes, sir.

Q Then afterwards?

A Then, afterwards, I heard again a noise, and I did not move. I did not move because I might be seen by the Japanese, and because I knew that there were Japanese there, the Japanese words, they had to shout very, very loud; that was why I knew that there were more Japanese there.

Q And what happened afterwards?

A Afterwards, when I [was] almost already awakened, I was opening my eyes small (demonstrating), then opening my eyes wide, a little wider, and I saw that “Oh,” we were covered with leaves of cocoanut, and chairs. Many chairs, they were bringing. Then, afterwards, I felt sore, I smelled gasoline, and I felt sore in one of my arms, this arm (indicating). It seemed to me that they sprinkled gasoline, that I felt sore in this arm (indicating left arm); then, I said, “God, please don’t let me see those Japanese. I do not like to be burned, when I am alive. I [would] like to die before I already burn.” Then, I [would have] liked to die at that time.

Q Were your hands tied at the time?

A Huh?

Q Where your hands tied at the time?

A No, sir; no were tied.

[p. 1809]

A Yes.

Q Do you mean to say that the Japanese poured gasoline on the chairs and other furniture?

A I only felt that my left arm was sore, I was not wet with gasoline, but I felt only that this was sore.

Q Was anybody burned after you were in that place?

A Burned?

Q Burned, yes.

A Yes, sir. Then, I heard an explosion — it seemed to me that it was burning already. Some were crying, “I am burning already; I am burning!”

Q You mean to say that you heard rolling flames?

A What do you mean by “rolling flames?”

INTERPRETER LAVENGCO: “I could hear the sound.”

A Then, afterwards, I heard no more noise of the Japanese, they were not speaking anymore, and then I pushed my right hand up and said, “God, permit me to go away from this.”

Q Yes, you have said that already. Were you able to escape?

A Yes, sir, I escaped.

Q Were you alone when you escaped?

A Yes, sir, I was alone.

Q Did you see dead bodies there in the place where you were?

[p. 1810]

Q You say that you were blindfolded by the Japanese?

A No —

Q How were you able to see these people?

A I was not — I took off my blindfold at that time, because I stood up.

Q You mean to say that you had free hands and you took off the blindfold, the piece of cloth blindfolding you?

A Yes, sir.

Q With your hands?

A Yes, sir.

Q And you saw the flames there, fire?

A When I stood up, I saw that it was burning already.

Q Burning?

A But I was apart from it —

Q Were bodies burning?

A Yes, bodies were burning, some dead, but others were not dead yet.

Q How many, more or less, was the number of persons you saw burning and who had already died, and those who were not dead yet? How many?

A I cannot tell you how many, because I was not searching for that. I was afraid that I went at once, that I might be caught by the Japanese again.

Q When you came to that place, did you see dead bodies already, lying on the ground?

A Huh?

[p. 1811]

A Dead bodies, yes, sir.

Q How many, more or less?

A More or less, about 50,but less than 50.

Q To what unit or branch of service did these Japanese that bayoneted you belong?

A To what?

Q To what unit, do you know? Who were they? Were they M.P.’s or Army soldiers, or Navy soldiers? Those Japanese that bayoneted you.

A I saw one M.P. with [a] long saber.

Q Was he an officer or a soldier?

A Officer, only one officer, with bars here (indicating left arm).

Q How did you know he was an officer?

A Because he had a long saber, and very many say that it was an officer with [a] long saber.

Q How about the rest?

A The rest did not have.

Q Were they plainclothes soldiers, or civilian Japanese, Japanese civilians?

A Khaki uniform; they were khaki uniforms.

MAJOR OPINION: That is all, sir.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: The Commission wishes to clear up a point.

Can you tell us the name and age of the youngest child who died on that day?

THE WITNESS: My youngest child? One year old.

[p. 1812]

GENERAL REYNOLDS: And the next youngest, please?

THE WITNESS: Five years old.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: Five years?

THE WITNESS: Yes, sir.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: And the next, please?

THE WITNESS: Nine.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: And the next?

THE WITNESS: Fifteen.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: Were there any others>

THE WITNESS: My mother.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: Your mother?

THE WITNESS: Yes, sir.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: In other words, there were four of your children and your mother who died on that day>

THE WITNESS: Yes, sir.

GENERAL REYNOLDS: That is all.

CAPTAIN REEL: No questions.