Nasugbu, Batangas in the 19th Century as Described by a Spanish Historian

In this seventh article of the series featuring the towns of Batangas as described by the Spanish historian Manuel Sastron, we focus on the western Batangas town of Nasugbu. The information is taken from Sastron’s 1895 book “Batangas y Su Provincia1” (Batangas and Its Province).

Sastron described Nasugbu as being a pueblo or town 71 kilometers from the town of Batangas, capital of the province. Measured on Google Earth, as the crow flies, the distance is roughly 58 kilometers.

He further stated that the pueblo was bounded to the north by the Province of Cavite; to the east by the Caytitingan River2; Lian to the south; and the sea to the west, with Fortune Island visible in the distance.

There was a main road that connected Nasugbu to the town of Batangas and all other pueblos of the province. This road, however, did not pass through Calatagan, which could be reached by way of a different route.

Like most other towns of Batangas, Nasugbu had a Municipal Court, a Justice of the Peace3, schools for both genders; and an outpost for the Guardia Civil or Civil Guard.

The Court House had been built with solid materials and was in relatively good condition. At the time, however, it was being occupied by officers of the Civil Guard, which as mentioned maintained an outpost in the town.

In contrast, the school building was made of light materials. By this, presumably Sastron meant it was built with wood and/or bamboo and thatched materials for roofing, as was typical of Filipino houses at the time.

The church in Nasugbu, along with the attached Parish House, were built with sturdy materials; even if, Sastron observed, the Parish House had started to look a tad on the dilapidated side. This, he said, was due to an abject lack of funds. Had funds been available, the parish priest, Fr. Leocadio Dimailig, would have put these to good use.

The most impressive and important building in the town, Sastron further wrote, was the hacienda or estate home belonging to His Excellency Don Pedro Roxas.

Nasugbu had added to its jurisdiction the village of Looc, which had enough inhabitants to have had its own chapel built. The chaplain and his assistants enjoyed the benefits of a subsidy granted by Don Pedro, whom Sastron described as “the great protector of the interests of his people.”

Looc also had its own school for children. The school operated with funds provided locally, presumably from Don Pedro. There were also two rivers and two navigable estuaries that flowed through the village, which had a small port of its own.

Sastron was also quick to point out that, despite Don Pedro’s extensive land holdings in the town, he neither desired nor aspired for an administrative role in the municipality. Suffice it to say that income from the Roxas estate filled the coffers of the Municipal Treasury. A modest and generous man, Don Pedro was always prepared to help Nasugbu in whichever way his help was needed.

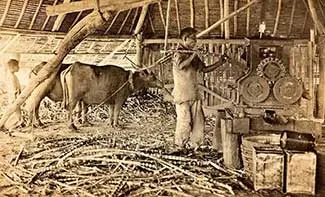

Nasugbu’s agriculture was dependent on rainfall, Sastron observed. The town’s primary produce was sugarcane; which was then converted into sugar and exported to Manila primarily by the company of Don Pedro.

The town also produced rice, corn, tobacco and monggo in much smaller quantities than sugar. It also apparently tried to jump into the coffee bandwagon that brought so much wealth to Lipa. By this time, however, thousands of coffee plants were either sick or dying from the bayongbong (a plant worm) infestation4.

Nasugbu’s mountainous areas, Sastron wrote, were thickly forested with a wide variety of valuable timber species: molave, dongon, acle, tindalo, lanote, banaba, bolongayta, camagong, soloin, palomaria, manga and others.

Curiously, while Nasugbu did not have a proper livestock industry, there were a lot of farm animals in the town, presumably used as beasts of burden in the farms.

Sastron noted that that the inhabitants of Nasugbu were “extremely docile” and “peace loving” that there were hardly any crimes committed in the town. They were also generally healthy, to an extent due to the fact that the town had in one Dr. Justo Panis an accredited doctor.

Nasugbu late in the nineteenth century was a flourishing town. Frequently anchored in its port were sail or steam ships to bring in our take out goods. Sastron concluded, however, that more infrastructures needed to be built to improve the town’s communications with other towns of the province for the betterment of Nasugbu’s inhabitants.

2 There are various references over the Internet to a Kaytitinga River in Cavite.

3 The “Juez de Paz” or Justice of the Peace was an arbitration court that tried to settle cases on the basis of conciliation between parties rather than legality. “Justice of the Peace,” Wikipedia.

4 In her 2003 dissertation entitled “Demythologizing the History of Coffee in Lipa, Batangas in the XIX Century,” Maria Rita Isabel Santos Castro noted that the decline of coffee plantations in Batangas was caused by a fungus.