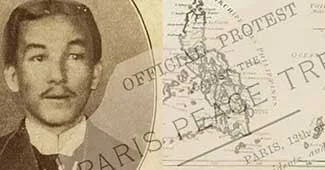

Felipe Agoncillo’s Official Protest Against the Treaty of Paris of 1898

[Keywords: Felipe Agoncillo, Treaty of Paris, Filipino Diplomat, Philippine Independence, End to Spanish Rule in the Philippines, American purchase of the Philippines from Spain]

Read: “Taaleño Felipe Agoncillo’s Failed Efforts at Securing Self Rule for the Philippines in 1898”

OFFICIAL PROTEST

AGAINST THE

PARIS PEACE TREATY

PARIS, 12TH OF DECEMBER, 1898

Their Excellencies, the Presidents and Delegates of the Spanish American Peace Commission, Paris.

The very noble and gallant General Emilio Aguinaldo, President of the Philippine Republic, and his government have honored me with the post of Official Representative to the very Honorable President and Government of the United States of America, devolving on me, at the same time, the duty of protesting against any resolutions contrary to the independence of that country which might be passed by the Peace Commission in Paris.

This has already terminated its sessions, in the resolutions passed cannot be accepted as obligatory by my Government, since the Commission has neither heard, nor in any ways admitted to its deliberations, the Philippine nation, who held and unquestionable right to intervene in them, in relation to what might affect their future.

I fulfill, therefore, my duty, when I protest, as I do in the most solemn manner, in the name of the President of the National Government of the Philippines, against any resolutions agreed upon at the Peace Conference in Paris, as long as the juridical, political, independent personality of the Filipino people is entirely unrecognized, and attempts are made in any form to impose on these inhabitants, resolutions which have not been sanction by their public powers, the only ones who can legally decide a future in history.

Spain is absolutely devoid of status and power to decide, in any shape or form, the before mentioned matter. The Union of Spain and the Philippines, was founded solely on to historical facts, in which the exclusive right of the Filipinos to decide their own destiny implicitly recognized.

First: The “Blood Treaty” (Pacto de Sangre) of the 12th of March 1565, entered into between the General Don Miguel Lopez de Legazpi and the Filipino sovereign, Sikatuna, a compact which was ratified and confirmed on the one side, by the King of Spain, Philip II, and, on the other side, by the Monarchs of Mindanao, Bisaya and Luzon and by the Supreme Chief of the Confederation, the Sultan Lacandola: proclaiming as a consequence, the autonomous nationality of the Kingdom of “New Castille,” formed by the Philippine Islands, under the scepter of the King of Spain.

Second: The so-called “Constitution of Cadiz,” in the discussion, vote, promulgation and execution of the Deputies and Filipino people took an active part; and by which constitution the nationality of “The Spains” was made effective.

But from the very first moment in which the Peninsular Public Powers attempted to impose their absolute sovereignty on the Islands, the Filipinos protested energetically by force of arms, and from the first attempt in 1814, the struggle in defense of their political personality was implanted.

When, in 1837, the violent deprivation of their rights was consummated, the Filipinos again protested, Spain sustaining against them a fratricidal and inhuman struggle, which has lasted from that time onwards up to the present day.

Falsehood, which always characterized the actions of the peninsular authorities, constantly hid from the world the fact of the real situation of force, which has lasted almost a hundred years.

At length, at the end of the present century, the Spanish forces have been completely routed by those of the natives, and Spain cannot now even allege the possession by her of the Islands; because the permanency of a handful of Peninsular soldiers, (approximately 400) who are holding out, besieged in one or two fortresses in the south of the Archipelago, cannot constitute such a right. The Spanish Government has ceased to hold any dominion by deed and by right; and the only authority which exists there and preserves order, is that constituted by the Filipinos, with the solemn sanction of their votes, the only legal fount of positive modern power.

Under such conditions, the Spanish Commissioners in Paris have not been able, within the principles of the Law of Nations, to give up or transfer what, if they ever had, they have actually totally lost before the signing of the Protocol of Washington and the arranging of the terms of the Peace Treaty in Paris.

The Filipino People who consented to the “Blood Treaty” and the “Constitution of 1812,” annulled those conventions, by reason of Spain not complying with her undertakings, and renewed their sovereignty by the solemn proclamation of the Philippine Republic on the 1st of August, 1898, and by the establishment of a government and a regular and well-ordered administration, created by the decisive votes of the natives.

If any juridical effect can be attributed to the Spanish action in the Peace Treaty, within the principles of International Law, it is the explicit renunciation of all future pretention over the land, the dominion and possession of which she has lost, and therefore is only of use to make the recognition of the corporate body of the Filipino nation, and that of their rights to rule effectively in respect of their future.

The United States of America, on their part, cannot allege a better right to constitute themselves as arbitrators as to the future of the Philippines.

On the contrary, the demands of honor and good faith impose on them the explicit recognition of the political status of the people, who, loyal to their conventions, were a devoted ally of their forces in the moments of danger and strife. The noble General Emilio Aguinaldo and the other Filipino Chiefs were solicited to place themselves at the head of the suffering and heroic sons of that country, to fight against Spain and to second the action of the brave and skillful Admiral Dewey.

At the time of imploring their armed cooperation, both the Commander of the “Petrel” and Captain Wood, in Hong Kong, before the declaration of war, the American Consul Generals Mr. Pratt, in Singapore, Mr. Wildman, in Hong Kong, and Mr. Williams, in Cavite, acting as international agents of the great American nation, at a moment of great anxiety, offered to recognize the independence of the Filipino nation, as soon as triumph was attained.

Under the face of such promises, an american man-of-war, the 'McCulloch,' was placed at the disposal of the said leaders, and which took them to their native shores; and Admiral Dewey himself, by sending the man-of-war; by not denying to General Aguinaldo and his companions the exacting office promises, when they were presented to him on board his flagship in the bay of Manila; by receiving General Aguinaldo before and after his victories and notable deeds of arms, with the honors due to a Commander-in-Chief of an allied army, and chief of an independent state; by accepting the efficacious operation of that army and those generals; recognizing the Filipino flag, and permitting it to be hoisted on sea and land,consenting that their ships should sail with the said flag within the places which we're blockaded; by receiving a solemn notification of the formal proclamation of the Philippine nation, without protesting against it, nor opposing in any way its existence; by entering into relations with those generals and with the national filipino authorities recently established, recognized without question the corporated body and autonomous of the people who had succeeded in their fetters and freeing themselves by the impulse of their own force.

And that recognition cannot now be denied by the honorable and serious people of the United States of America, who ought not to deny nor discuss the word given by their officials and representatives in those parts, in moments so solemn in gravity for the American Republic.

To pretend to put now in question the attributes of such public functionaries, after the danger, would be an act of notorious injustice, which cannot be consented to by those who have the unavoidable duty of preserving unstained the brilliant reputation of the sons of the great nation founded by the immortal Washington, whose first glory was, and has always been, the constant fulfillment of their word of honor.

It must be remembered here that the Filipinos did not fight as paid troops or mercenaries of America. On their arrival, they only received a reduced number of arms, which were delivered to them by the order of Admiral Dewey. The arms, ammunition and provisions, with which the Filipinos have since sustained the war against the Spanish forces, were acquired, some by their gallantry, and others bought with their own funds, these latter being exclusively provided by the Filipino patriots.

And it would not be noble to deny now, after having used the alliance, the courage, loyalty and nobility of the Filipino forces in fighting at the side of the American troops, lending them a decided support, both enthusiastic and efficacious.

Without their cooperation and without the previous siege, would the Americans have been able so easily to gain possession of the Walled City of Manila?

They could, who can deny it, have destroyed it by bombardment, but without the foregoing armed deeds, and without the rigorous circle in which the Spanish army was enclosed, the pretense of the attack and surrender which took place could not absolutely have been realized.

Admiral Dewey gloriously destroyed the Spanish squadron, but he had not disembarking forces, and could not inconsiderately dispose of his ammunition and provisions; and under such conditions, the support, which, as companions in arms, was lent to him by the Filipino generals and their forces, is a positive and undeniable advantage. Without them, General Anderson’s troops and those which afterwards were disembarked, probably would not have been able to have arrived in Manila before the suspension of hostilities and the signing of the Protocol of Washington.

Truth and sincerity in their places.

Now, if the Spaniards have not been able to transfer to the Americans the rights which they did not possess; if the former have not militarily conquered positions in the Philippines; if the occupation of Manila was a resulting fact, prepared by the Filipinos; if the international officials and representatives of the Republic of the United States of America offered to recognize the independence and sovereignty of the Philippines solicited and accepted their alliance, how can they now constitute themselves as arbiters of the control, administration and future government of the Philippine Islands?

If, in the Treaty of Paris, there had simply been declared the withdrawal and abandonment by the Spaniards of their dominion – if they ever had one – over the Filipino territory; if America, on accepting peace, had signed the treaty, without prejudice to the rights of the Philippines, and with the view of coming to a subsequent settlement with the existing Filipino National Government, thus recognizing the sovereignty of the latter, their alliance and the carrying out of their promises of honor to the said Filipinos, it is very evident that no protest against their action would have been made. But in view of the terms of the 3rd article of the protocol, the proceedings of the American Commissioners, and the imperative necessity of safeguarding the national rights of my country, I make this protest, which I wish to comprise for the beforementioned reasons, but with the corresponding legal restrictions, as against the whole action taken and the resolutions passed by the Peace Commissioners at Paris, and in the treaty signed by them. And in making this protest, I claim, in the name of the Filipino nation, in that of their President and Government, the fulfillment of the solemn declaration made by the illustrious William McKinley, President of the Republic of the United States of North America, that, on going to war, he was not guided by any intention of territorial expansion, but only in respect to the principles of humanity, the duty of liberating tyrannized people, and the desire to proclaim the unalienable rights of sovereignty of countries released from the yoke of Spain.

God keep your Excellencies many years.

FELIPE AGONCILLO

2 “Honor in the Dust: Theodore Roosevelt, War in the Philippines, and the Rise and Fall of America’s Imperial Dream,” by Gregg Jones. 2012.

3 “Protesta oficial contra el Tratado de Paz de Paris,” online at Duke University Libraries Digital Repository.