The Capture of Mt. Malepunyo East of Lipa and the End of Japanese Resistance in Batangas in 1945

[In this article: Mount Malepunyo, Lipa Batangas, 11th Airborne Division, Talisay Lipa Batangas, Sapac Lipa Batangas, World War II Batangas]

That mountain due east of the city of Lipa in Batangas which even many locals erroneously refer to as Mt. Malarayat is, in fact, a mountain range called Mt. Malepunyo; and Malarayat is just a hill to its side. Malepunyo was, in 1945, where vicious fighting took place so that the United States Army could put an end to Japanese resistance in Batangas.

In his 1948 book1 documenting the exploits of the 11th Airborne Division, Major Edward M. Flanagan Jr. narrated the sequence of events. After what some World War II documents referred to as some of the fiercest fighting in the Western Pacific Theater of War in Mt. Maculot, the United States Army faced just one final concentration of Japanese troops in Batangas. This was at Mt. Malepunyo, and according to Flanagan the order from the army brass was succinct: “Capture Mount Malepunyo and destroy all the Japs thereon.”

|

| Original caption: Mortars of the 511th Infantry Regiment. Image source: The Angels: A History of the 11th Airborne Division 1943-1946 by Maj. Edward M. Flanagan Jr. |

The 187th Glider Infantry Regiment, having just successfully accomplished the order to wipe out Japanese resistance at Mt. Maculot, had no time to rest and was sent to Tiaong to block the retreat of the Japanese from Mount Malepunyo. The 188th, meanwhile, was transferred to Alaminos and ordered to attack the mountain from the South. The lead group in the assault on Malepunyo, however, was the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

Flanagan described the group’s task:

“They were to attack east along the Malarayat Hill Canyon, then turn north to join the 188th Infantry and a special task force composed of Company C of the 511th, Troop F of the 7th Cavalry, and a platoon of Battery D of the 457th with two 75mm pack howitzers for assault guns. This force was called Ciceri Task Force for Major John Ciceri, its commander.”

|

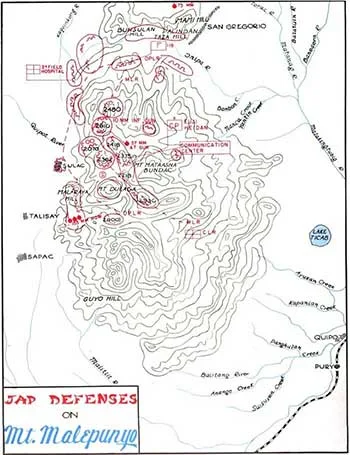

| A map of Japanese defensive positions on Mt. Malepunyo. Image source: The Angels: A History of the 11th Airborne Division 1943-1946 by Maj. Edward M. Flanagan Jr. |

READ: “Finding Barrio Sulok, the Strategic Barrio in WWII Santo Tomas, Batangas.”

The Americans surrounded the mountains with light and medium artillery and continuously pounded the Japanese positions. Pack howitzers3 were dismantled, taken up the mountains and reassembled. Tanks, chemical mortars and fighter-bombers were also used.

Soldiers of the 511th, observing that the Japanese scampered to their caves at the sound of approaching fighter planes and quickly came out to man the outer defenses as soon the planes left, positioned themselves closer and mowed down the Japanese with gunfire as they came out.

But the Japanese were far from done. Holding higher ground, they slowed down the advance of American forces with snipers and machine gun fire. In one particular incident in what was called Hill 2610, men of the 511th were surprised to receive gunfire from carefully hidden apertures in the underground Japanese command post. The Japanese had to be flushed out using flamethrowers. The Americans were not without casualties. Wrote Flanagan:

“Before being mowed down, they (the Japanese) pulled one last trick which cost us casualties. Several of the Nips, as they ran out of the caves, threw large demolition charges into the air, where they burst, wounding and killing our men as well as themselves.”

“On the next day, Norman Martin, his ears well pinned back, sallied forth with his captured Japanese mortar and two captured Japanese woodpeckers to investigate a report of a large Japanese force some six or seven miles away. He was accompanied by a crew of Headquarters Battery men, with a few willing assistants from the gun batteries. They located the Japanese force, encircled them in the night, and at dawn let loose with all their captured weapons. They then moved in and counted. Ninety-five Japs lay dead, and only Rauschendorff was wounded.”

2 “US Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific, Triumph in the Philippines” by Robert Ross Smith, published in 1993 by the Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, Washington D.C.

3 Pack howitzers were guns that “could be broken down into several pieces to be carried by pack animals.” Wikipedia.